Cover photo courtesy of Sami Raad

Hof — It’s hard to know what kind of loss war leaves behind until it touches the shape of your city. Not just its people, or its streets, or the silence that follows after shelling—but the things that gave it meaning.

Its face.

Its posture.

Its language of stone and steel.

On July 16, 2025, Israeli airstrikes struck the heart of Damascus. The target was the old General Staff building, once the brain of Syria’s military command. But around it—within walking distance—are places that meant far more to me than any officer, president, or war.

That building stands in the middle of Umayyad Square. It’s not a square, really—it’s a massive roundabout. But the name has stuck for generations. It’s the kind of place I passed a hundred times without stopping, but each time I did, I noticed it. Because you couldn’t not.

Umyyad Square (circle) after and before fall of Assad, National Library (left) General Staff Building & Sword of Damascus (right)

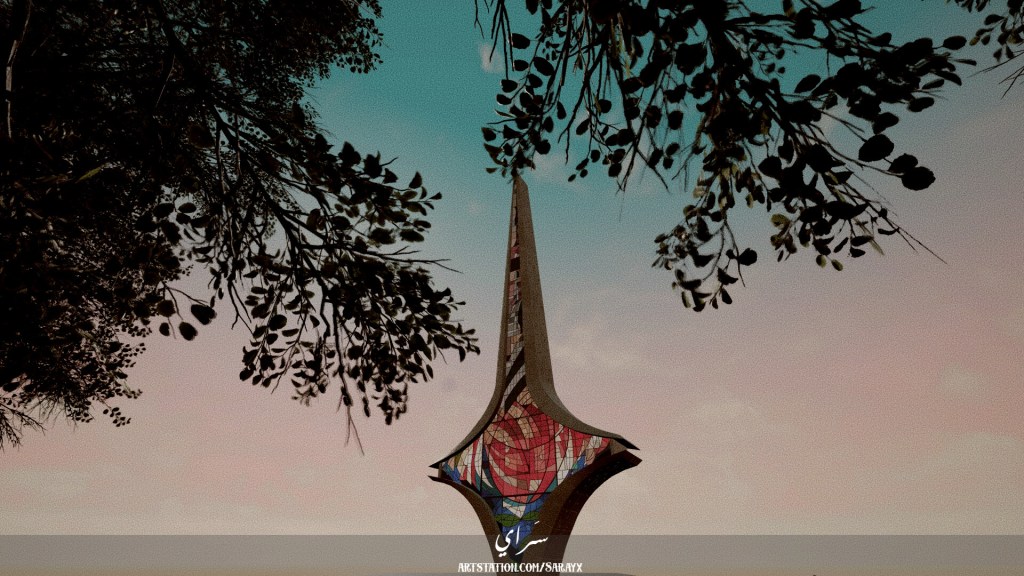

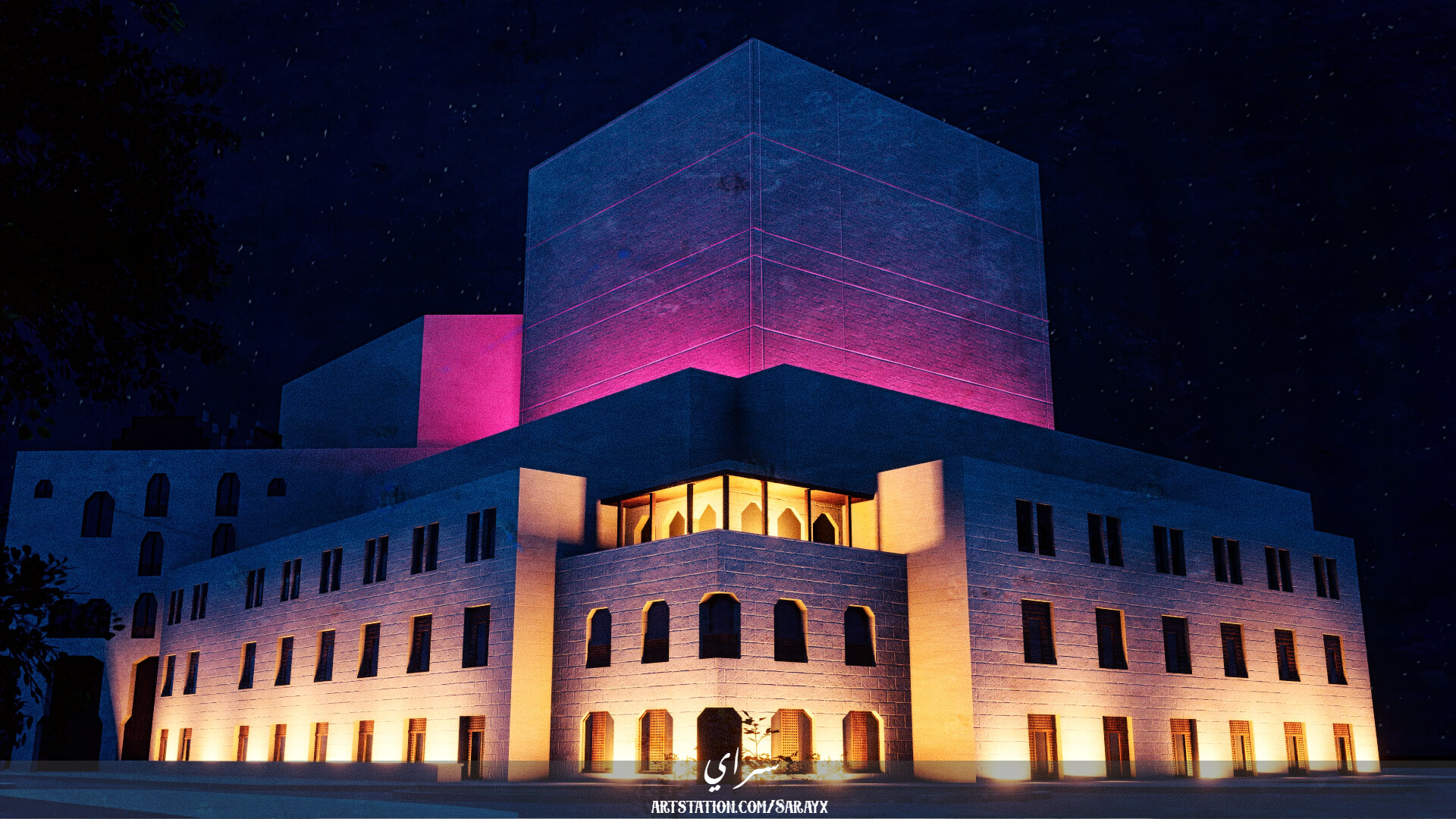

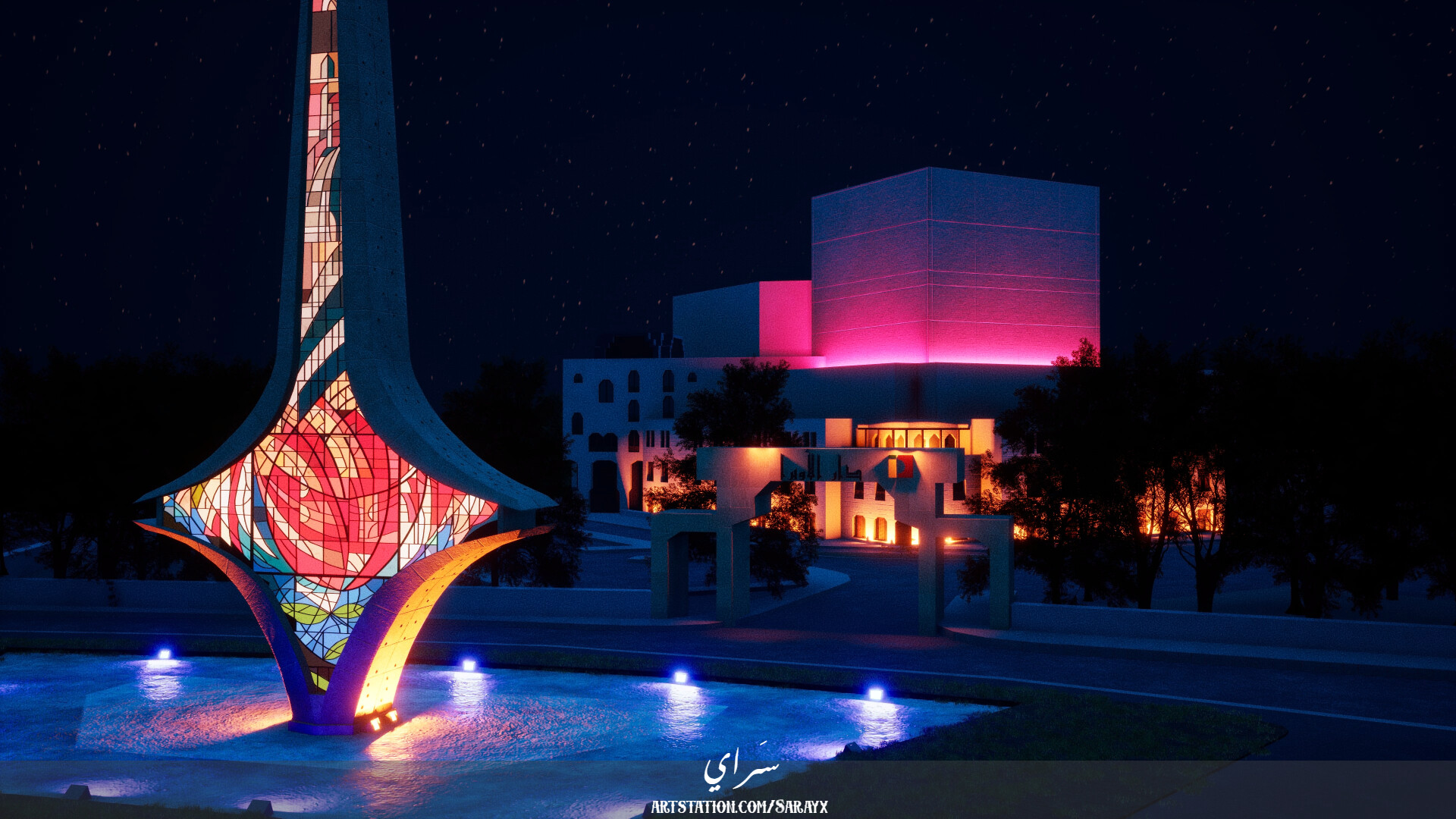

To the right stands the Damascus Opera House, one of the few places in the Arab world where you could watch a classical concert, a symphony, or a play performed under full stage lighting. To the left: the National Library, the largest public archive in Syria—quiet, cavernous, filled with rare manuscripts, legal records, and books you couldn’t find anywhere else in the country. In front of both, towering like a declaration, is the Sword of Damascus—a massive monument shaped like a blade, held up by a bronze arm bursting from the ground.

It’s nationalistic, yes. Grand. Maybe over-the-top. But it’s also ours.

Sword of Damascus, and the Opera House

Behind the monument, just across the circle, is the old Syrian TV building—grey, boxy, stained by time. It housed not only regime propaganda, but also the first studios where I learned what broadcast meant. Where young editors cut their teeth, where journalists pushed as far as they dared.

And perched above it all, on the western hills, is the People’s Palace — the crown jewel of Syria’s modern architecture.

Commissioned by Hafez al-Assad, Syria’s last brutal but competent leader, the palace was so grand that even he chose not to live in it. Instead, he named it the People’s Palace — reserving it for ceremonies, summits, and hosting foreign dignitaries. For decades, the average Syrian only saw it from afar, its silhouette watching over the capital like a stone promise.

Bashar al-Assad used it more frequently, but when he fled Damascus in 2024, his personal belongings were found in the Presidential Palace downtown —not here.

Now, with the regime gone, this palace must finally live up to its name. It should be reclaimed, restored, and opened to the public — transformed into a national museum, a park, a gathering place for the Syrian people to meet, reflect, and rebuild.

This part of Damascus isn’t ancient. It’s not behind the Roman Wall. It’s not carved in stone or scented with jasmine. But it is modern Syria—or what modern Syria once hoped to be.

Built mostly between the 1960s and 1980s, this part of the city is where Bauhaus lines met Arab ambition, where Brutalism got softened by wide boulevards, and where a young republic tried to imagine itself as something bold, civic, sovereign.

It’s not perfect. It never was. The state that built these buildings also built prisons, crushed dissent, and silenced too many voices. But those structures are still part of the story. And stories need places to live.

When I saw the footage of the strike—live, from multiple cameras—it hit me hard. Not because of the blast itself. I’ve seen worse. I’ve lived through worse. But because I knew exactly what could be lost next.

It doesn’t matter if the strike technically hit a military command. What matters is how close it came to wiping out the last civic face of a broken capital. And it reminded me of something deeper: No city deserves to be erased.

Not Damascus.

Not Gaza.

Not Tel Aviv.

There are places in every city that carry more than function. They carry memory. Aspiration. Belonging.

When you destroy them, you don’t just punish the present— you rob the future of any sense of continuity.

Ten years ago, I wrote an article wrestling with my own support for the Syrian army. It was never about loyalty to Assad. It was about fear. The fear that if the state collapsed, the idea of Syria would collapse with it.

In 2024, that collapse came anyway. Bashar fled. The army dissolved. And now Syria’s fate is being debated not in Damascus, but in Doha, Jerusalem, Ankara, and behind conference doors in countless capitals.

A new government sits in the capital. But it has no constitution, no popular legitimacy, no sense of place. And once again, we hover on the edge of all-out war—this time with fewer illusions.

So I’m writing this to say one thing:

Preserve the city! Preserve what’s left of its civic core. Because if Damascus is reduced to rubble like Gaza, if its modern face is flattened in the name of security or retribution— there will be nothing left to build on.

I’m calling on UNESCO to expand its protection of Damascus—to include not just the ancient souqs and citadels, but also Umayyad Square and its institutions.

I’m asking the Syrian authorities to relocate their military and political operations outside of densely populated and historically significant areas.

And I’m asking the State of Israel to refrain from targeting this city’s civic infrastructure, no matter who is in charge—because some things are bigger than governments.

This isn’t about excusing war crimes or denying security threats. It’s about drawing a moral boundary that war should not be allowed to cross.

Because once you erase a city’s memory, you’ve already won the war—but at the cost of humanity.

We can’t afford to lose Damascus. Not like this.

Relevant Links

When Healing Became Another Battle

3 thoughts on “Damascus Brutalist Legacy”